By Walter Bachmann, Prof. Kristjan Jespersen

For years, green bonds captured the imagination of investors and issuers alike, promising a genuine win-win outcome: capital would flow into projects with measurable environmental benefits, and the firms raising that capital could do so at a lower cost than in the conventional bond market. This attractive combination, widely referred to as the green premium or greenium, implied that investors were willing to accept slightly smaller yields in exchange for the satisfaction of financing climate solutions. The narrative proved compelling. Policymakers welcomed it as evidence that financial markets could help close the climate-finance gap, companies used it to signal corporate responsibility, and asset managers viewed it as a practical way to align portfolios with sustainability mandates.

Early empirical studies appeared to confirm the promise. Analyses of primary-market data from the mid-2010s reported yield discounts of three to eight basis points for green instruments relative to comparable vanilla issues. As a result, the labelled market expanded rapidly. By 2023 outstanding green bonds totalled roughly six hundred billion dollars, and the structure migrated from being a niche offering to becoming a standard tool for investment-grade corporations, financial institutions, and sovereign treasuries.

Whether the pricing advantage survived this remarkable expansion is the central question addressed here. This study assembles an issuance-level dataset covering almost fifty thousand bonds launched between 2015 and 2025 in Europe, North America, and China, of which around 2 thousand were formally labelled as green. These three regions dominate both global bond volumes and global greenhouse-gas emissions, so results carry relevance beyond local markets. Ordinary least squares regressions and issuer-fixed-effects panel models are employed to estimate the difference in initial yield spreads while controlling for rating, tenor, currency, coupon type, and issuer characteristics.

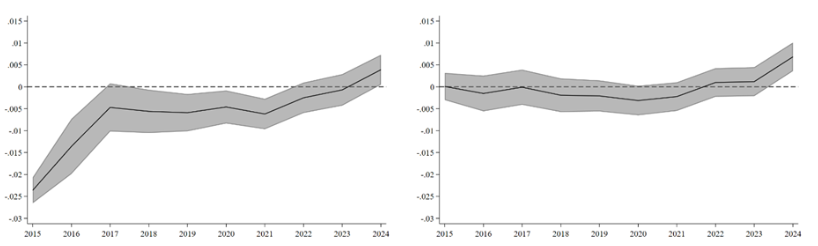

Results from the cross-sectional ordinary least squares model reveal a clear trend. From 2015 through 2017 the coefficient on the green label is negative and statistically different from zero, confirming that green bonds were indeed issued at lower yields. Yet the absolute size of the discount narrows every year, falling from roughly six basis points in 2015 to a statistically negligible level by 2020. By 2024 the coefficient has turned positive, indicating that issuers of green bonds now pay a slightly more. Confidence intervals widen in the later years, suggesting growing dispersion in investor valuations as the market matures and supply becomes abundant.

Panel estimates reinforce the narrative but add nuance. Once constant issuer characteristics are stripped out, the green-bond premium oscillates around zero with greater variability than in the pooled sample. The discount disappears roughly two years earlier than in the cross-sectional case, while the subsequent up-turn begins in 2021 and reaches significance in 2024. These findings imply that unobservable differences between repeat issuers played a role in the early period but faded as disclosure standards converged and investors gained experience with the product. Furthermore, sectoral breakdowns deepen the picture. When combined the high-emitting industries such as oil and gas, metals, and chemicals never achieve a material greenium. Their environmental projects may be essential for the transition, yet investors appear unconvinced that a green label overrides broader balance-sheet exposure to carbon risk.

Three structural forces explain the vanishing greenium. First, supply has caught up with demand. When labelled bonds were scarce, impact-oriented investors competed for limited paper, pushing up prices. By the early 2020s the market had produced enough volume that scarcity ceased to be a driver. Second, transparency improved. Harmonised taxonomies, second-party opinions, and post-issuance allocation reports reduced information asymmetry, leaving little hidden value for investors to monetise. Third, macroeconomic conditions shifted. Rising interest rates, elevated inflation uncertainty, and renewed focus on credit fundamentals compressed risk premia across asset classes, making non-pecuniary benefits a luxury many investors were unwilling to fund through lower yields.

The erosion of the pricing advantage has practical consequences. For issuers, the green label no longer reduces interest expense in a predictable way, but it still confers reputational capital and may help diversify the investor base. Regulators are also moving toward mandatory sustainability disclosure, implying that future issuance choices will be influenced as much by compliance considerations as by cost. For investors, the disappearance of the yield concession heightens the importance of rigorous impact assessment. In the contemporary market the premium that matters is credibility. Transactions backed by verifiable environmental metrics, stringent use-of-proceeds frameworks, and transparent governance continue to attract strong demand, even if they no longer command higher secondary-market prices.

The green-bond market has transitioned from novelty to norm. The financial incentive that once spurred issuers has largely evaporated, replaced by intangible benefits linked to brand value, stakeholder expectations, and regulatory readiness. Yet the instrument retains strategic importance as a conduit for climate finance. Its standardised documentation, earmarked proceeds, and investor familiarity make it uniquely suited to mobilise private capital at scale. Policymakers seeking to revive any lost cost advantage may consider tax incentives, credit guarantees, or structured co-financing that reward measurable emissions reductions. Ultimately, the path from green label to green impact will depend less on marginal changes in coupon rates and more on the integrity and transparency of the projects being financed.

About the Authors

Walter Bachmann recently completed a MSc Finance and Investments with a Minor in Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) at Copenhagen Business School (CBS). During his time as a student, he also worked as a research assistant for the Nordic ESG Lab and as M&A Analyst at LNP Corporate Finance. This September he will commence his second master’s degree at Imperial College Business School, where he will dive deeper into sustainability and financeWith a finance degree already in hand, the additional qualification from Imperial, combined with his prior ESG experience, positions him well to advance in sustainable finance.

Prof. Kristjan Jespersen is an Associate Professor in Sustainable Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the Copenhagen Business School (CBS). Kristjan is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School (CBS). As a primary area of focus, he studies the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance. He has a background in International Relations and Economics.